Death is Young

This is my monthly art-related newsletter/blog. Usually, its contents include new art I've made, news about exhibitions, and other art-related ideas I've been thinking about. However, August has been pretty rough, and so I wrote about pet death, family, and life history. If you'd rather look at the art I've been working on, please check out my new art-only instagram account, @edengallanter.

This month my sweet, two-year-old cat died of cancer.

One day she was running and playing, and jumping into my lap every time I sat down. The next day she started acting sick, and after two subsequent visits to the hospital, the doctors told me that she had cancer—lymphoma. It was incurable, and she was only going to get worse. We arranged immediately for a vet to come to our home to euthanize her, and she died in my arms. It was so shockingly fast.

If you've ever had a pet to whom you have a special connection, who follows you around the house, who trusts you, and just wants to be near you all the time, you already know that this pet feels like family. Whatever the world family has come to mean to you, it acts as a soft, warm cocoon around your heart. Family, whether made up of biological relatives, caretakers, close friends, partners, or pets, is one of those parts of life that appears to me to be fundamental, and vitally important for survival.

I am very close to my parents, and I know how lucky I am that this is so. Many people I know have bad luck in this regard. They have parents they are unable to connect to, or unable to respect. Some have parents who were cruel, or violent, or neglectful, or who abandoned them. I am fortunate to have parents I can love and admire, and who have always, always strived to be loving, supportive and faithful to me.

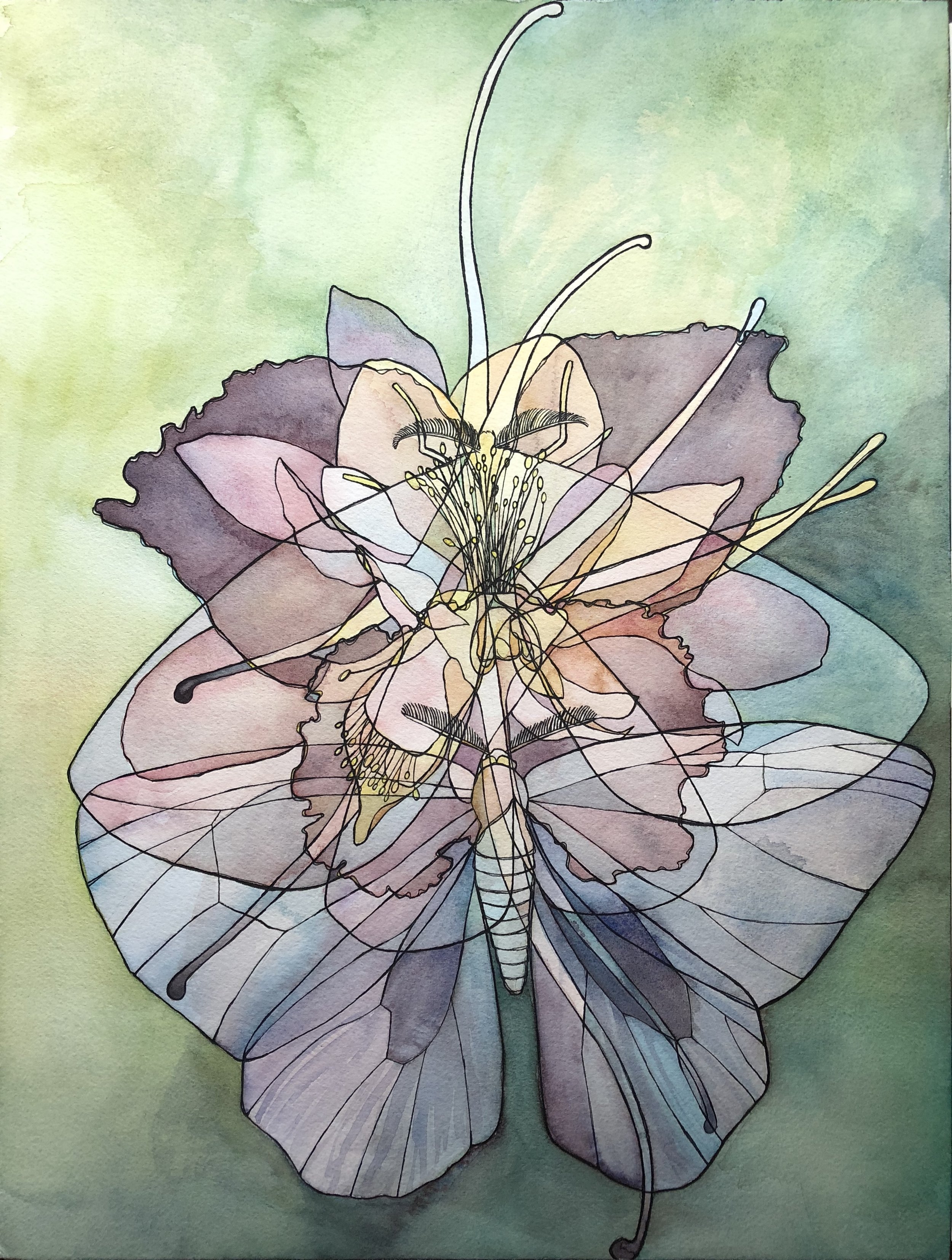

My Father. Charcoal on paper.

My parents are also quite old—especially my father, who turned ninety this year. I am writing his biography. This is both intensely pleasurable for my father, and incredibly difficult. There are few happy memories of childhood and youth to detail; an overwhelming number of his recollections are marked by loneliness and tragedy. It is an incredibly intimate experience to do this with him. He has now told me stories he hasn't told anybody else. Sitting with him, holding his hand, sometimes crying with him, while listening to these memories that have been buried for so long, touches me deeply.

In writing a story, we are always haunted by the story's end.

Both my parental grandparents died suddenly of cardiovascular disease in their fifties, his elder brother in his forties, and my father himself survived a triple bypass when I was in the third grade. Nevertheless, he is ninety, and I couldn't help wondering what it would be like when my dad passed away, as I was spending my last remaining days with my sick cat.

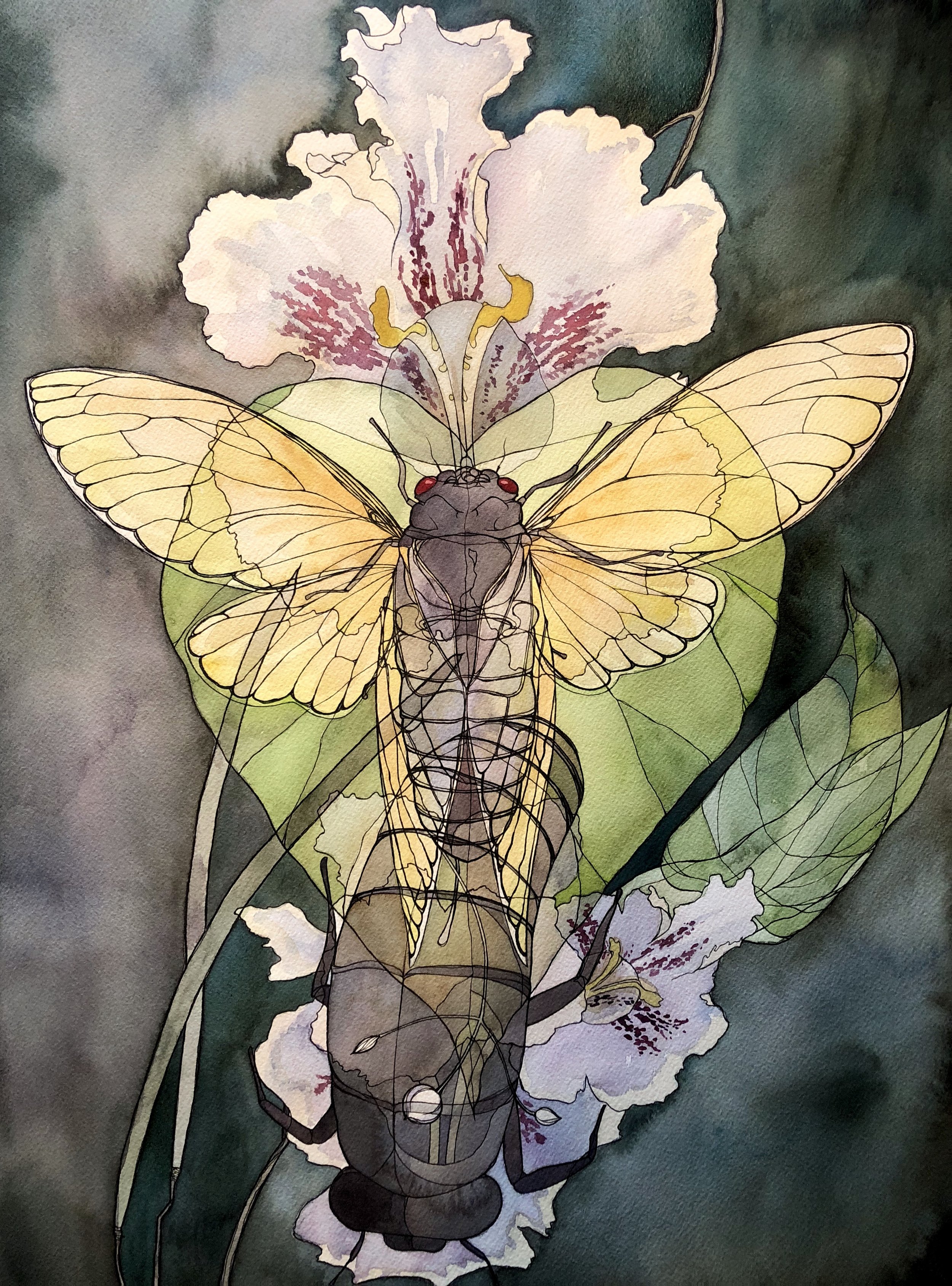

Anushka. (August 2016 – August 2018)

There is no real way to prepare for tragedy. I believe that the best we can all do is try to face the inevitable, and accept the fact that the world we live in gives us an illusion of control on a truly immense scale. There was no way for me to prepare myself for losing a very young and beloved pet to cancer. All I could do was focus on what mattered, when it happened. I wasn't ready to say goodbye, but I knew that the most important thing was my responsibility to take care of her. In this case, that meant protecting her from suffering any more pain. I stayed awake every night to sit with her. I could barely eat—food choked me. Grief can fill you up and bury you at the same time. The world around us faded. I couldn't even feel the chill of the house, sitting on the floor with her at 4:00 AM. I sat there, with my dying cat leaning against my leg, and I thought about what it would be like to lose my father.

The culture I live in has shielded itself from death. Death happens in hospitals and dark alleyways. Open casket funerals are increasingly rare in this country. The processes of mortality are more secreted away from us that they used to be. But isn't death as natural as the ocean? Can't death be as gentle as the wilting of cut roses, which leave behind a subtle fragrance even after they have faded? It seems to me that life is very short. Living in perpetual fear of tragedy isn't realistic, but at the same time I believe I ought to make the most of whatever time I have with the people I love—my little family, my close friends, and the small number of people who have profoundly inspired and changed the course of my life.

I don't have an answer for grief, or for the inevitability of future grief when you let yourself love someone. Grief is a living creature, with its own logic, its own desires, its own food. All we can do is care for it as tenderly as we would care for anything else we loved.

suppose

Life is an old man carrying flowers on his head.

young death sits in a café

smiling,a piece of money held between

his thumb and first finger

(i say “will he buy flowers” to you

and “Death is young

life wears velour trousers

life totters,life has a beard” i

say to you who are silent.—”Do you see

Life?he is there and here,

or that, or this

or nothing or an old man 3 thirds

asleep,on his head

flowers,always crying

to nobody something about les

roses les bluets

yes,

will He buy?

Les belles bottes—oh hear

,pas chères”)

and my love slowly answered I think so. But

I think I see someone else

there is a lady,whose name is Afterwards

she is sitting beside young death,is slender;

likes flowers.

- ee cummings, Tulips & Chimneys